Umberto Eco wrote – I think it was in “Travels in Hyper-reality” – that there are some things that people can’t say in a post-modern world. His example was that you can’t just say, “I love you”, because those words have been spoken so often, for example by actors in daytime soaps and characters in true romance novels, that it just sounds insincere or else naive when someone says it in real life.

Eco said a young man wanting to declare himself to his loved one would have to take into account all the other times those words have been said or typed, and express his emotion while at the same time acknowledging that the words have become a cliché.

Brady & Chloe, from “Days of Our Lives”. Oh god, how they could love

So instead of saying, “I love you”, he should say, “Well, as Lohengrin once said to Elsa, in the words in which Brady opened his heart to Chloe in “Days of our Lives”, as Paul McCartney’s songs so frequently declare, I love you.”

And so, Eco argues, the young woman will still receive the emotional message, but be charmed and impressed at the way her young man has managed to surround his emotional confession with quotation marks and irony, deftly avoiding cliché.

Eco was one of the least wanky of the post-modernists, but that still left him a lot of room to be wanky in.*

Eco’s claim about the impossibility of saying “I love you” would be fatuous even if it were true.

But the problem of fatuity doesn’t really arise because, first and foremost, it’s complete bullshit.

The words “I love you” are still available to be spoken with sincerity and emotional force, regardless of all the other ways they might be spoken. Anyone who really has trouble saying those words because someone used the same words in a bad soap opera is as nuts as those Christians who think their marriages will become meaningless if gays and lesbians are allowed to marry.

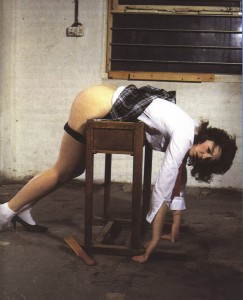

The school skirt she bought mail order. But finding a desk that looked school-y, at about the right height: that took serious shopping

So take that phrase, “oh please sir, not the cane; i’m a good girl really”. Let’s say it’s spoken by a woman in her thirties who has bought herself a saucy pleated skirt and a white blouse, and she’s about to bend over a school desk.

She’s just waiting for the command of her dom, or master. Anyway, her lover, who is standing just behind her, flexing a cane.

When she begs not to be caned, she may or may not be being sincere.

If getting the cane is part of her life, then the chances are that even if she doesn’t enjoy the cane strokes at the instant they land, she likes being a submissive woman whose discipline and control includes the cane, and she especially likes being a submissive woman who’s just been caned. Once the immediate pain dies away to warmth, and she’s being comforted in her dom or master’s arms, having just been caned can be a happy, loving, sexy feeling.

Still, she might genuinely be afraid of the caning just before it begins. She knows that begging not to be caned won’t work, except possibly to get extra strokes, but perhaps it’s sincere.

But when she says she’s a good girl really, what in the world do those words mean? Not in the fantasy they’re playing with, but (ahem) really?

* What did I mean, Eco “was”? Well, post-modernism is dead, and a lot of the key pomo writers are dead too, but Eco is still alive. Still, like a lot of people who were once liable to refer to something like massacres in Syria as “discourse”, and to talk about living in “post-modernity”, he doesn’t talk in pomo cliches any more.

Watching a former post-modernist get reminded of something they once said about Lacan, say, is rather like watching a dog-owner walking away from their dog’s turds on a neighbour’s lawn, pretending they never knew about it and it’s got nothing to do with them.

“No. At the office. Ana, you’re a bad girl.”

“No. At the office. Ana, you’re a bad girl.”