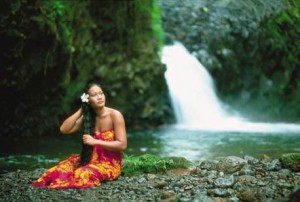

In spite of the power she had over me, I didn’t think she was using her beauty in a knowing way. I suspected that she didn’t really believe she was beautiful, or know the effect she could have on men. And she didnt see me as a man. Not that she liked men much, I thought. She liked boys.

I wasn’t much older than her, but I wouldn’t quite have been a boy even if she’d thought of me as human at all. I didn’t wear uniform, as a probation officer, but I might as well have. I was part of the horrible thing that had happened to her – cops, courts, geek with clipboard – simply because she was young, pretty and Samoan.

So I held on to my clipboard, coughed till my voice sounded solid again, and started asking her questions about her family, who she lived with, who she hung with, and what plans she had for jobs, education and so on.

I didn’t put my reservations about the police charges into my report to the judge. It would have been pointless because she’d pled guilty, even though she shouldn’t have. She didn’t want to get involved in the fuss that would begin if she changed her plea at this stage. I’d tried to talk her into getting a new lawyer and going for a re-trial because she hadn’t been properly represented, but she didn’t want to do it.

And if she wasn’t going to change her plea, it would have just caused her trouble if I commented on the police conduct. The judge who was going to sentence her really hated lawyers, let alone junior probation officers, who accused the police of misconduct. He didn’t want to hear it, and he let it be known that it would backfire on their clients.

This girl – her name was Tiana, though she called herself Ana – was very vulnerable to a bit of judicial shittiness. Technically, she could only stay out of jail if she showed contrition. So if I argued on her behalf that she should never have been arrested and that the charges should have been dropped, that wouldn’t be contrition.

This girl – her name was Tiana, though she called herself Ana – was very vulnerable to a bit of judicial shittiness. Technically, she could only stay out of jail if she showed contrition. So if I argued on her behalf that she should never have been arrested and that the charges should have been dropped, that wouldn’t be contrition.

I’d be putting her in jail.

So I wrote a report calculated to keep her out of there. I claimed that she’d fallen into bad company but that there were positive influences in her family. She was taing active steps to find employment. This is the sort of stuff judges love. I argued for community supervision rather than a fine. She was broke, and unemployed. She couldn’t pay a fine.

The judge accepted my recommendation. I’d got paid less and done her much more good than her defence lawyer. I expected she’d go on the client list of a wiley old Quaker called Ethan who had an office down the corridor from mine. Ethan did a good line in gentle-but-scary father-figuring, that kept most of his clients from getting themselves into further trouble.

To be continued.