Years ago, when I was just 23, I worked as a probation officer. My job was to interview people who’d committed crimes: that is, they’d pled guilty or been found guilty, but they hadn’t been sentenced yet.

I’d go and see them with their families, their employers if they had a job, and their teachers if they were at school.

Then I’d write a report on why they’d committed their crime, and what sort of influences in their life put them at risk of re-offending, and what influences might help them get out of further crime. I’d make a recommendation for the judge, about what the best sentence would be. Judges usually took this advice.

I’d usually recommend that they not get sent to jail, because there was plenty of evidence that jailing people only made it more likely that they’d reoffend, and that the offences they committed after they’d been to jail were usually more serious than there ones that they’d committed before. So most often I argued for keeping them in the community, but with supervision.

The supervisor would be a probation officer, and he or she had the power to tell the criminal where they could live, who they could associate with, and in some circumstances, with a Court order, we could make the person come in and do supervised work for the community, like cleaning graffiti off people’s walls, that kind of thing.

Most of my clients were sad people. They’d had terrible lives, by the time they were 18 or so. Many were about as intelligent as a plate of cat food, and they often had untreated psychiatric illnesses. They could be helped, if someone got them help, but they’d never been diagnosed or treated.

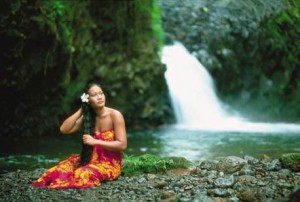

Then I had a new client. She was 18, just five years younger than me. She was a Samoan girl, and although she didn’t really know it – she didn’t know anything good about herself – she was shockingly, heart-stoppingly beautiful.

I’ll leave off here. To be continued.